© Stacks Bowers

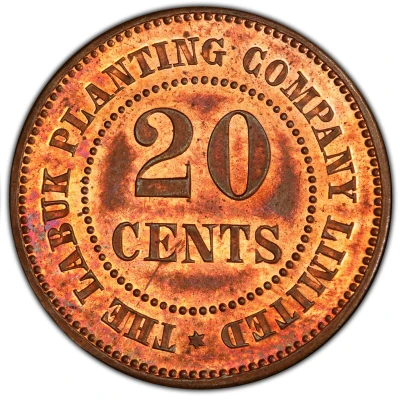

1 Dollar - Labuk Planting Company Limited ND

| Copper | - | 28 mm |

| Location | Malaya and British Borneo (British Malaysia) |

|---|---|

| Type | Trade tokens › Work encampment, mine and wage tokens |

| Years | 1880-1899 |

| Value | 1 Dollar |

| Currency | Dollar (1953-1967) |

| Composition | Copper |

| Diameter | 28 mm |

| Shape | Round |

| Technique | Milled |

| Orientation | Coin alignment ↑↓ |

| Demonetized | Yes |

| Updated | 2024-11-14 |

| Numista | N#329949 |

|---|---|

| Rarity index | 97% |

Reverse

Denomination in Chinese Characters

Script: Chinese (traditional, regular script)

Lettering:

壹

圓

Translation: One Dollar

Edge

Plain

Comment

PLANTATION TOKEN COINAGEAn unusual form of private currency also circulated in British North Borneo. These were tokens issued by the various plantations involved primarily in the production of tobacco and rubber. Similar private token coinage and paper money was also in circulation in the Netherlands East Indies (Indonesia), at planta tions in Java, Sumatra, and Borneo (Kalimantan).

In North Borneo a number of plantations issued metal tokens, in denomina tions of one cent, three cents, five cents, ten cents, twenty cents, twenty-five cents, fifty cents, one dollar and two dollars. Denominations up to five dollars were permitted by the Government, but apparently no metal tokens were issued in this high value. In addition, paper tokens were apparently issued by at least one plantation, though at present no issued cample is recorded to have survived; only a few unissued or "specimen notes exist in private collections. Normally, metal coins or tokens tend to survive in larger numbers than the paper ones: when an issue is being called in and redeemed, a metal token might be kept as a souvenir, but the paper issues tend to be redeemed. However, the fact that no signed and issued paper token has yet to be located from any British North Borneo plantation is quite unusual; if such a piece could be found it would be a rarity.

The most unusual aspect of this private coinage is that the tokens were given legal status; this meant that the Government recognized each plantation's issue, and retained some control over it. In other States plantations could issue as many tokens as the local people would accept. If the plantation's reputation was not good, the circulation of tokens would be limited to the labourers who were actually paid with them.

In British North Borneo, during the twenty years after 1882, any person employing more than one hundred workers was allowed to issue tokens. Permission had to be obtained from the Governor, and examples were to be sent to the Treasury in Sandakan, and also to the nearest District Office. The maximum value of tokens allowed to be issued by an employer was 10,000 dollars, quite a considerable sum at the time.

As various abuses to the token system became known, ordinances dated 1903, 1906 and 1912 came into effect covering the issue and circulation of tokens: By 1920 it was decided that the use of tokens would be abolished, and from that year every issuer had to withdraw one fifth of his total issue. These redeemed tokens were to be sent to the local District Office; thus by the end of 1924 the use of tokens for payments was terminated. Interestingly, Muzium Sabah (The National Museum of Sabah) has among its holdings bags of heavily circulated tokens from two or three of these plantations. These tokens had apparently been stored at the Treasury, and undoubtedly represented a part of the 1920-1924 redemptions. As there are relatively few plantation tokens in private hands it would seem that the vast majority of redeemed pieces were either destroyed under the Company Administration, or quite possibly were melted down by the Japanese during their long occupation the Japanese were constantly on the lookout for supplies of scrap metal to be used for their war effort.

However, some tokens have survived, and several catalogues have been made of them. The first was by the Dutchman Van Der Chijs at Batavia (Jakarta) in 1896. This was followed at a considerably later date by the Americans Verner Scaife and W.W. Woodside in the 1950's, and the Englishman Major Fred Pridmore in 1962. However, the largest and by far most complete catalogue of these tokens has been prepared by Saran Singh, AMN, of Kuala Lumpur, as part of his major work "The Encyclopedia of The Coins of Malaysia. Singapore and Brunei 1400-1986" Collectors and other readers interested in further research are referred to this excellent work.

Tokens were issued by the following companies; the location if known is listed in brackets after the company name:

Borneo Labuk Tobacco Company Limited (Two Rivers, Labuk)

Labuk British North Borneo (Labuk)

The Labuk Planting Company Limited (Toon Good, Labuk)

London and Amsterdam, Borneo Tobacco Company Limited (Mengharap)

London Borneo Tobacco Company (Ranau)

Cadei Pitas Estate (Pitas)

Sandakan Tobacco Company Limited (Sandakan)

Sandakan Tobacco Company Limited (Batuh Puteh Estate)

Tenom Rubber Company Limited (Tenom)

New Labuan Borneo Tobacco Company Limited Estate Shop (Labuan)

The New Darvel Bay (Borneo)

Tobacco Plantations Limited (Lahad Datu)

Ramie Fiber Company Limited Borneo (Ranau)

Melalap Estate (Tenom) Kimanis Rubber Limited (Kimanis)

Pitas and Nicolina Estates of H.C. Eduards Meyer (Pitas)

The Cowie Harbour Coal Company Limited (Silimpopon)

Jellani Estate, which may have been in Borneo, or possibly in Malaya.

There were undoubtedly other plantations that issued tokens as well, but of which no examples have yet been recorded or traced.

Source: Brunei and Nusantara, History in Coinage; William L.S. Barrett, Brunei History Centre, 1988

An interesting extract from the archive:

In 1890 "Manila Hemp" was cultivated in British North Borneo by the Labuk Planting Company, Limited, and the fibre raised on their estates was satisfactorily reported on by the Rope Works in Hong-Kong.

In, view of the present scarcity of live-stock, hemp, which needs no buffalo tillage, would seem to be the most hopeful crop of the future. It will probably advance as fast as sugar cultivation is receding, and command a good remunerative price. Moreover, as already explained! not being distinctly a season crop as sugar is, nor requiring expensive machinery 10 produce it, its cultivation is: the most recommendable to American colonists.